| CROMFORD VILLAGE in DERBYSHIRE |

|

|

|

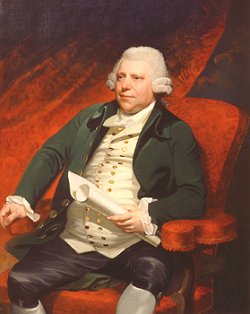

SIR RICHARD ARKWRIGHT - THE FIRST GENERATION

Sir Richard Arkwright transformed the small village of Cromford when he established his cotton spinning mills here between 1771 and 1784. He built houses for the workers, a hotel, a new corn mill and established a market. Willersley Castle and St Mary's Church were started by him and finished after his death on 3 August 1792. To find out more about Sir Richard Arkwright in Cromford visit the History Page |

Portrait by Joseph Wright of Derby c1785.

Portrait by Joseph Wright of Derby 1790. On the table is a model of his spinning machine. He had by now secured legal rights to his inventions, been awarded a knighthood and the office of High Sheriff of Derbyshire. |

|||

|

Masson Mill was the only mill to continue in production for any length of time, finally closing in 1991. In 1946, after the end of the Second World War, a booklet was produced by the Sir Richard Arkwright & Co Ltd, Masson Mill, to mark the end of the war and the beginning of a new peacetime prosperity. There are few things which we are more inclined to take for granted than cotton, and yet few things have made a greater difference to ordinary, everyday life. It was only just over two hundred and fifty years ago that we began to import cotton in any great quantity, and we did not use much ourselves until the middle of the 18th century. Even then the goods produced were of an inferior kind, because we did not know how to spin yarn strong enough to make the warp threads in the cloth, so we had to use linen for that purpose, and the result was an inferior mixture called fustian. At first all the work was done at home. In many places in Derbyshire and the north of England merchants gave out the raw cotton to the workers, and the whole family, from grandparents to small children, combined in the various processes. The cleaning, carding and spinning was done by the women and children, while the men and older boys did the weaving, and it is easy to see that it took six or seven workers to make enough yarn to keep one weaver busy. It was all done by hand, and when the cloth was finished it was collected by the merchant, who paid for the work which had gone into making it. By 1750 several attempts had been made to invent machinery to make the manufacture of cloth quicker and easier, but none had been successful. It was our own Richard Arkwright who was mainly responsible for the first great improvements and discoveries which were made. Richard Arkwright was born in Preston in 1732, the thirteenth child of a poor man. This did not seem a very fortunate beginning, and for many years he had a hard struggle. He had very little schooling; indeed he gained most of his education late in life, for when he had become rich he still used to practise grammar and spelling, until, we are told, he wrote a very good business letter. He was always interested in mechanics, but when he was quite young he was apprenticed to a barber, and when he had finished his time he set up his own little shop in a cellar in Bolton. Here he soon showed the enterprise which was to be the foundation of his fortune by putting out a sign "Come to the subterraneous barber; He shaves for a penny". When he was about 35 he obtained the secret of a process for dyeing human hair, which was very valuable as wigs were then in fashion. All this time he had been making mechanical experiments. His wife had died and in 1761 he remarried. The second Mrs Arkwright did not approve of him wasting time with machinery when he should have been building up the barber's business, so one day, while he was out, she burned all his models. This seems to have been the reason why he left home and started to travel about the countryside buying hair, which he dyed and sold to wigmakers. He had spent all his life among textile workers and knew a great deal about their trade and during his journeys he met still more of them. By this time he was working on the idea of a spinning machine which, by taking the cotton sliver over two sets of rollers, the second revolving faster than the first, would make a yarn much better than could be spun by hand. At last it was finished, but he was too poor to put his machine into production himself, so he had to find somebody who could give him the financial help he needed. After a number of setbacks he at length met Mr Jedediah Strutt of Nottingham, a hosiery manufacturer who had himself adapted the stocking-frame to make the famous "Derby rib." He was very impressed by Arkwright's invention and he and his partner, Mr Need, agreed to finance it, and the three men entered into partnership. At last the invention was patented, a frame was made after Arkwright's model and production started in 1769, in Nottingham. At first the frame was driven by horse-power, but this proved too expensive, so the firm moved to Cromford in 1771. During his journeys round the countryside Arkwright must have seen what an excellent place this was for a mill, * with the river to drive the new machinery. A year or two later a larger mill of six storeys was built, and for this the water from local streams and from the Wirksworth mines was used, being carried over the road by a culvert to fall on to and turn the mill wheel. As this water was at a higher temperature than normal it never froze in winter, so that even in the coldest weather the mill was in no danger of having to stop work; it also prevented the adjoining canal from freezing over, so that in those days before the railways there was always easy transport available to and from the mill. So Arkwright and his partners began to make the new yarn, which was much stronger and more uniform than was possible when spun by hand, and could be produced in much larger quantities. This made it cheaper than any other, but manufacturers of cloth were prejudiced against it and would not buy it. This meant that Arkwright had to dispose of it elsewhere, so his partners decided to weave it into calico in their new mill which they built at Belper. This was the first cloth ever to be made in England entirely out of cotton, for the new yarn was so strong that it could be used even for the warp as well as the weft. It was also very suitable for hosiery, and so was of great assistance in the stocking trade in Derbyshire and the Midlands. By this time the other manufacturers realised that Arkwright's frame had come to stay. They were jealous of his success and combined against him, and, accusing him of having borrowed his ideas from other inventors, brought a case into court to have his patents set aside. After several years they succeeded in getting this done, but as by this time Arkwright was a very wealthy man and the patents were soon due to expire, he could afford to let the matter rest. Soon after setting up business at Cromford he built Masson Mill, which later became his chief factory, and in a few years had extended his interests to other towns, including Bakewell and Wirksworth, which made him one of the most important manufacturers in the country. These mills employed many people. In those days, as we have seen, even small children had to work for their living by helping their parents in making cloth at home, so now they began to be sent to work in the cotton mills which rapidly grew up all over the north of England. Those who worked for Arkwright were fortunate, for he was a kindly employer. He had probably never forgotten his own early struggles against poverty, for at a time when many of his rivals had no thought for anything but making money, he took an interest in his work people. His factories were much cleaner and better kept than was usual at that time; he built houses for his employees which were described as models of comfort and neatness, and his apprentices were well looked after. Other men had their share in inventing the machinery which has revolutionised our lives, but it was Richard Arkwright who first realised how great the changes were that they brought about. Instead of making their cloth at home where they could work as they pleased, people now went into the factories, and because the new frames were driven by water and later by steam, these mills had to be built by rivers or streams, which would provide them with power. He was the first man to organise the work to suit the new conditions, and many textile manufacturers came to visit his mills to learn his methods. All these changes brought one great benefit; cotton goods became much cheaper and more plentiful, until they were within the reach of everybody. We today find it difficult to imagine a world without inexpensive cotton goods, and to realise what a difference they have made. Three hundred years ago, while the rich wore silks and velvets, ordinary people had to be content with less expensive and less attractive materials. Linen was not cheap, and most people wore woollen cloth for their outer garments at least. This meant that clothes were heavy, hot in summer, and difficult to launder; so health suffered. As a result of good, cheap cotton materials, life became much more pleasant: people certainly were much healthier, for they could have more underclothes, which could be washed easily and often; that too made the housewife's work easier.Everybody could have sheets on their beds, and could afford things like curtains and tablecloths, so that homes were more comfortable. Life would be very different without cotton. The above article is reproduced from a booklet produced in 1946 by the Sir Richard Arkwright Co Ltd, Masson Mill. * More is now known about the early history of the Cromford Mills. They were powered by water wheels utilising water from Cromford Sough and Bonsall Brook. |

|

|||

|

Sir Richard Arkwright had one son, Richard, by his first wife Patience Holt; and one surviving daughter, Susanna, by his second wife Margaret Biggens.

The child in the portrait is Mary Ann, who was to marry her cousin Peter Arkwright. |

Left - From "The Hurts of Derbyshire" Derek Wain |

|||

|

19 December 1755 - 23 April 1843 Richard Arkwright (junior) was born on 19 December 1755 in Bolton, Lancashire, the son of Richard Arkwright and his first wife Patience Holt. His mother died when Richard was only ten months old, and his father re-married, in March 1761, Margaret, the daughter of Samuel Biggins of Leigh, Lancashire.?> Richard's half sister Susannah was born the day after his sixth birthday, two other half sisters died in infancy.

Sir Richard Arkwright died in 1792, leaving the greater part of his estate to his son Richard, who was by then a wealthy mill owner in his own right. Richard Arkwright junior married Mary Simpson of Bonsall in 1780, and the couple had eleven children. Elizabeth Arkwright: born 1780

|

"Richard Arkwright, his wife Mary and Child", painted in 1790 by Joseph Wright of Derby The child is Mary, aged 2 years.

Left - Portraits by Joseph Wright of Derby, 1791 |

|||

|

Left to right: Robert, Richard and Peter. Left to right: Elizabeth, Charles and John.

|

||||

|

The following article about Richard Arkwright Junior by David Jenkins was published in Reflections magazine in May 2001. It is reproduced here by kind permission of Reflections magazine. When Sir Richard Arkwright, king of cotton spinning, died in 1792 his only son, another Richard, took stock of his life and elected to change its principal direction. Born in Bolton on 19 December 1755, Richard was brought up by his father, his mother having died when he was only a few months old. When he was six his father remarried, and Margaret Biggens became his stepmother. By the time young Richard was in his early teens his father had set up his mill at Cromford and moved to live at The Rock. Here the boy started to learn the intricate details of the trade and particularly the commercial niceties. Quiet by nature, he had inherited much of his father's business acumen; by the time he was in his mid-twenties he was able to buy from his father the Manchester mill in Millers' Lane. Here he entered into partnership with the Simpson brothers, who managed the business while Richard continued to live in his newly acquired house at Bakewell. Despite the interruption of the American War of Independence the cotton boom continued, and in *1781 the young Richard, who had married Mary Simpson a year earlier, was ready to buy the corn mill at Rocester, which he promptly converted to a spinning mill. Here, with Richard Briddon of Bakewell, who held a third share in the enterprise, he continued to prove his managerial skills and in 1787 bought the site of the Cressbrook Mill, built by his father and recently destroyed by fire. At Cressbrook he re-employed William Newton (the Minstrel of the Peak) who was newly available after working on the Crescent at Buxton, to rebuild the mill and extend the housing for the pauper apprentices. But he was not happy just running factories, and after three years at the Manchester mill he sold out his interest at a handsome profit, for £20,000, paid in instalments over seven years. Meanwhile his father had been knighted, but he died in 1792. Much of his estate was left to the daughter of his second marriage, his grandchildren, and to charities, but the residue, including a number of the manufactories, passed to his son Richard. It was at this point that Richard, aged 37, took stock and decided to concentrate on landed property and banking. Almost immediately he disposed of most of the mills, and this turned out to be a wise move as the post-Napoleonic recession set in. The funds released by these sales were invested in Consolidated stock or ploughed into property. Already Richard held £40,000 in the Funds, and by the time he died he was the largest holder in the kingdom. Much of Richard's wealth stemmed from his banking business, Richard Arkwright & Co. of Wirksworth. His Croesus touch extended into the making of private loans to some well-heeled borrowers: Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (anxious to conceal her gambling debts from her husband), Sir Thomas Hunloke, Henry Cavendish, William Lowe, the sixth Earl of Chesterfield, and many local businessmen. He had little interest in the status significance of landed property, although he did move to Willersley Castle, where he was intensely interested in developing the gardens. But he wanted to ensure his children enjoyed the privileges of the gentry and to this end he had started by buying Darley Hall, followed by Skerne, near Driffield, and Skerne Hall Garth, together with the two paper mills and a flour mill. This outlay was matched in 1796 by the purchase of Normanton Turville in Leicestershire for Richard, his eldest son. The acquisition of a small estate at Crich followed and then, in 1809, he bought the Herefordshire estate of Hampton Court for £230,000, for his son John. Joseph, his youngest son set up home in Harlow in Essex, while Charles chose Dunston Hall at Tatentile, Staffordshire. But it was during the purchase of Sutton Hall in Temple Normanton (later occupied by Robert Arkwright) that Richard's great wealth was highlighted. As the bidding rose, the auctioneer became concerned that the unknown bidder sitting in his simple buff coat and fawn breeches might not be able to pay the deposit, let alone the capital sum. Richard took from his pocket a banknote for £20,000 stating: "There are only four of these printed, the other three are at home". He disliked London, which he visited infrequently, but he enjoyed Cromford. At Willersley he had a small retinue of nine servants, and a coachman. His needs were simple, and occasionally he would be mistaken for another gardener as he worked in the exotic greenhouses, the house and gardens being opened to the public on one day each week. Public service had no appeal for him, though he unfailingly supported the Tories and was very proud when his son Richard became MP for Rye. Surprisingly, the Times carried no obituary when, aged 87, he died from a sudden stroke. The insignificant notice of his death made no reference to his extensive property holding, disposed of in a 16-page will, or of his being by far and away the wealthiest commoner in Britain with an estate of over three and three quarter million pounds (over £150 million at today's prices). His diffident exterior masked his financial genius, and he was happier in the company of his thirty-nine grandchildren than in the halls of power. It is only a pity that his business success is so overshadowed by that of his father. The above article by David Jenkins reproduced by kind permission of Reflections magazine. * According to R S Fitton in his book "The Arkwrights, Spinners of fortune", Sir Richard Arkwright bought Rocester corn and fulling mills in 1781 and converted them to cotton spinning. In 1783 he sold out to his son Richard junior. - YD |

Left -

Left - From "The Hurts of Derbyshire" Derek Wain |

|||

| Derbyshire |

THE ARKWRIGHT SPANISH "COUNTERMARKED TOKEN" COIN The coin on the left is an extremely rare Spanish countermarked token coin which was issued to the workforce at the Cromford mills. In the early 19th century the expansion of the factory system caused an increase in demand for small change with which to pay wages and not enough silver coinage was being produced. Mill owners started to import foreign coins and impress their own stamps onto them. This coin is stamped "CROMFORD DERBYSHIRE 4/9" The coin was thus worth four shillings and ninepence, about a week's wage at the time.

On the right is an example of a Spanish coin similar to the one countermarked in Cromford. Also dated 1802 and with a milled edge, it has the same inscription "CAROLUS IIII DEO GRATIA", and bears the king's portrait. King Charles IV was king of Spain from 1788 to 1808. The coin was minted in the Spanish colony of Mexico. The coin can be seen in the museum at Masson Mill, Matlock Bath. There is another example in Derby Museum. |

Left - |

||

|

Joseph: 1791 - 1864. Joseph became the vicar of Latton, Essex and rector of Thurlaston in Leicestershire. He married Anne Wigram in 1818 and Anne: 1794 - 1844. Anne married Sir James Wigram of Walthamstow in 1818 and they had 4 sons and 5 daughters. James, the heir, married Margaret, one of Peter's daughters. Frances: 23 Aug 1796 - 4 Nov 1863. Frances was an invalid and did not marry. Harriet: 1798 - 7 Nov 1815. Harriet died aged 17. |

Left - From "The Hurts of Derbyshire" Derek Wain |

|||

|

17 April 1784 - 19 Sept 1866 Peter Arkwright was the fourth of the eleven children of Richard Arkwright Junior and his wife Mary. He was born on 17th April 1784 at Bakewell where his father owned the spinning mill and the mill at nearby Rocester. The family moved to Rock House in Cromford on the death of Sir Richard in 1792, and they moved into Willersley Castle when it was finally completed in 1796. That same year 12 year old Peter was sent to Eton with his older brothers Richard and Robert. The letters Richard and Peter wrote to their father from school show that the boys had an easy relationship with their parents. There were requests for money so the boys could go rowing, enquiries about the welfare of their horses at Willersley, and gossip about the masters and fellow pupils from Derbyshire families, including Hurt, Cavendish, Crompton and Wilmot. The boys played football and had music lessons. They seem to have enjoyed good health although Peter had to miss lessons for a while because of a thorn in his leg. The dates of forthcoming holidays and how they were to make their way home, either by mail or post chaise, was a frequent topic. There was no reprieve from school work however, as Mr Ward, the vicar of Cromford, gave them tuition in the holidays. Peter was the only one of the Arkwright boys not to go to university, his brothers all going up to Trinity College, Cambridge. Instead he stayed at Cromford and joined his father in running the family mills. On September 2nd 1805 he married his cousin Mary Anne, the daughter of Charles and Susanna Hurt of Wirksworth. His father gave him £500 on his marriage and made him his business partner. Two years later he gave him £3,000 for furniture. Peter and Mary had sixteen children, 13 of whom survived childhood: Frederic, Mary Anne, Edward, Henry, Alfred, James Charles, Ferdinand William, Susan Maria, Fanny Jane, Margaret Helen, Augustus Peter, John Thomas, and Caroline Elizabeth. In 1812 the Bakewell mill was conveyed to Peter and his brother Robert as co-partners, but was managed by Robert, who lived at nearby Stoke Hall. The brothers also owned and ran the two Cromford mills, and the nearby Masson Mill: the entry in Pigot & Co's Commercial Directories of 1821-22 and 1828-29 for the Cromford mills stated "These works are now in the proprietary of Messrs Robert and Peter Arkwright"; Steven Glover in 1829 referred to the extensive cotton mills belonging to Messrs R and P Arkwright. He added "These mills, and those of Masson, erected a little higher up the River Derwent, belong to and are worked by the grandsons of the eminent founder, who employ nearly 800 persons." But by 1835 Pigot stated "these works are now in the proprietary of Messrs Peter Arkwright & Co". Robert gave up his interests after the death of his brother Richard in 1832 when he took over the running of Richard's estates at Sutton Hall. |

Left - |

|||

|

THE DECLINE OF THE CROMFORD COTTON SPINNING MILLS Peter Arkwright was born in 1784, thirteen years after his grandfather had opened the first cotton spinning mill at Cromford. The mill site had been expanded with the building of a second mill, warehouses, workshops, offices and a mill manager's house; Masson Mill was built at Matlock Bath. Richard Arkwright had achieved commercial success and built up a personal fortune, and was knighted for his work in the cotton industry. Cotton mills based on his factory system and employing the water frame and other machines he devised to mechanise the spinning process were established around the country, especially in Lancashire, which became the centre of the industry. His inventions and factory system were copied in Europe and America. Meanwhile, the mills at Cromford, the birthplace of this revolution in the cotton industry, fell into decline, and finally closed during Peter Arkwright's lifetime. The years from the outbreak of war with France in 1793 had seen a steady decline in the economy, with the cotton industry badly affected. Five years later Arkwright Junior was complaining that many mills were stopping production, while others were shortening their working hours and undercutting prices. Profits fluctuated wildly and in 1819 the Arkwrights recorded their first ever loss. But 1823-24 saw a brief boom in the industry: banks had plenty of money to lend following the freeing up of overseas trade. This resulted in a surge in mill construction in Lancashire. As the new mills were established because it was easy to borrow money, not because of increased demand for the product, another slump in the cotton industry resulted with losses again recorded. Another factor in the decline of the cotton spinning mills at Cromford was the continued use of the water frames installed by Sir Richard. A more efficient variant of the frame called the throstle had been taken up by other mills, and competitors had also adopted an improved version of Crompton's mule in large steam-powered factories. Although the Cromford frames were well maintained and produced good hosiery, it was difficult to compete with more efficient methods of production. By 1829, the mills were producing hardly any profit. Sir Richard Phillips, in his book 'A Personal Tour through the United Kingdom', published in that year, passed through Cromford, and commented that "the present Mr Arkwright, son of Sir Richard, is between seventy and eighty.... His habits lead him to continue in business, though the profits are now trifling. Those of his father and his own, formerly, were 2 or 300 per cent, but competition has now rendered them nearly nominal". But the final closure of the Cromford Mills was brought about by the decrease in the water supply from Cromford Sough, the underground tunnel constructed between 1673 and 1682 to drain the Dove Gang lead mine. Work had begun on the Meerbrook Sough in 1772 with the aim of draining the whole of the lead mines in the Wirksworth area. One of the main shareholders was Francis Hurt of Alderwasley (the father of Charles who married Susanna, daughter of Sir Richard). By 1830 it had dramatically reduced the flow from Cromford Sough which powered the waterwheels at Cromford. The Arkwrights took legal action to safeguard the mills but judgement was given against them in the Court of Exchequer in 1839. On Saturday 21 September 1844, the mills stopped working for the first time; production petering out over the next few years. Only Masson Mill, which was powered by the River Derwent, remained in production. It seems that the Arkwrights preferred to see the closure of the Cromford cotton mills rather than drive the frames with steam engines. Richard Arkwright Junior was in his old age during the period of decline and died on 23rd April 1843 aged 87, so Peter Arkwright must have had the final decision on the mills' closure. Today Meerbrook Sough still discharges 12-20 million gallons a day into the river Derwent at Whatstandwell. |

||||

|

BUSINESS AND PUBLIC LIFE Fortunately for many years the Arkwright fortunes had not been dependent on cotton. The family had various other sources of income. This probably influenced the decision to let the mills at Cromford close: it was not financially viable to turn to steam power and income from the mills was only a small part of the family's wealth. From 1787 Peter's father, Arkwright Junior, was buying Consolidated Annuities. By 1822 he had become a government stock millionaire, and had acquired landed estates on which he settled his sons. One of Arkwright Junior's ventures was the bank founded at Wirksworth by John Toplis in 1780. In 1804 he became a partner in the bank, and Arkwright Toplis & Co became Richard Arkwright & Co in 1829, three years after Toplis's death. The partners were Arkwright and his sons Peter and Charles, each holding a third share in the total capital. By 1843 this amounted to £51,157. Arkwright also had investments in Derbyshire turnpikes and canals, and in railways. He had ten shares, and Peter had five, in the Cromford Canal Company. Arkwright was also a money lender on a large scale. Peter and the other Arkwright children benefitted from their father's generosity throughout their adult lives. In 1833 each of Arkwright's five sons, (Richard had died the year before), was given £3,000, and from 1834 each received £2,000 a year. In addition £20,000 was given to Robert, Peter, John and Charles in 1811, and again to each of his sons in 1822, 1828 and 1840. In 1838 Arkwright gave each of his adult children a £10,000 bank note at Christmas. Elizabeth and Anne received £15,000 on marriage and a generous yearly allowance. It could be said that Peter Arkwright had an easy life, being born to wealth and with a continuous supply of money from his multi millionaire father. But he may have felt he was living in his father's shadow, perhaps not having full control of the family businesses - His duties started at the age of 19 when he and his brother Robert were commissioned as captains in the Militia in 1803. Threatened with invasion by revolutionary France, Prime Minister Pitt had brought in a Bill for the raising of a volunteer force by voluntary contributions. A Volunteer Corps of Infantry in Derbyshire was raised following a meeting in Derby of forty-two of the most important people of the county on 30 April 1798, which Arkwright Junior attended. Arkwright Junior contributed £2,000 to the force and the Cromford mill workers collected £45 10s 1d between them. Only Richard of the Arkwright brothers was active in politics: he was Tory MP for Rye in Sussex for nine years. In 1832, the year of the first election after the Reform Act, Peter voted for the Conservative candidate, Sir Roger Greisley, who failed to win a seat. His father, Arkwright Junior, did not vote. At a Conservative dinner at the Red Lion in Wirksworth to celebrate the birthday of the Duke of Wellington, E M Mundy in a toast to Richard Arkwright Junior described him as one "whose influence has always been exerted in defence of Conservative principles, and the father of children educated in the same principles." Peter Arkwright replied that although his father was a staunch Conservative, he troubled himself little about politics. This would seem to be Peter's attitude also; however he played a full part in carrying out his duties as a member of the higher reaches of landed society, for which his education had prepared him. He served as a Justice of the Peace, High Sheriff and Deputy Lieutenant of Derbyshire. In Cromford he continued the support of the school which his father had established in 1832. Two years later the Derby Mercury reported: "On Saturday the girls belonging to the school, assembled at their room at the school, and proceeded to Rock House, the residence of Peter Arkwright, Esq. where 122 sat down to tea on the lawn in front of the house. Every attention that hospitality could dictate, was paid to them by Mrs. and the Miss Arkwrights." Children who attended school had to pay a small weekly charge. This was not enough to pay for the maintenance of the school and the teacher's house, the difference being made up by Peter Arkwright. On the death of his father on 23 April, 1843, Peter was 59 years old. He finally succeeded to the the Cromford and Willersley estates, together with the estates and mills at Marple and Mellor, the Manchester warehouses and various properties, including the paper mill at Masson, and mineral rights in and about Cromford and Wirksworth. His brothers each received the estates on which they were settled. For each there was a legacy - £40,000 for Peter, and a further £263,745 when the residue of the estate was divided. Peter Arkwright was involved in the development of the railway line which ran from Ambergate to Rowsley and was opened in 1849. He was indirectly responsible for the siting of the railway station in its present position. There was a conflict of opinion as to the siting of the station, originally it was to be at the south end of Cromford Meadows, with a new road to link it to the turnpike road, and a new canal wharf built at the station. Peter objected to this plan, preferring to build sidings from the proposed station to the existing wharf. Failure to agree led to the opening of a temporary station in the cutting approaching Willersley Tunnel, and this eventually became the official station. In 1850 a deputation of Cromford trades people expressed their concern over the lack of parcels and goods facilities. Arkwright insisted the line should be for passengers only, in order to protect his interests in the canal. Only parcels from John Smedley's Lea Mills were allowed. After his father's death Peter Arkwright held the gift of the living of St Mary's Church in Cromford, which meant he appointed the vicar, and contributed to his stipend and to the upkeep of the church. He was also responsible for the enlargement and alterations to the church in 1858-9. The chancel, the west portico and the gallery being added and the windows of the nave enlarged. FAMILY MAN

At the time of the 1851 census Peter was described as a Banker, living at Willersley Castle with his wife Mary and daughters Fanny Jane and Caroline. Two other daughters were visiting: Susan Maria with her husband Rev Joseph Wigram, the Archdeacon of Winchester; and Margaret Helen who had left her husband, James Wigram, at home, but had brought along his butler Augustus Pountaine. James Wigram was Margaret's cousin and a nephew of both Peter Arkwright and the Rev Joseph Wigram. Also present were Richard Simpson, a magistrate from Lancashire with his two daughters, Jane and Anne. These were probably relations as Peter's mother was a Simpson before marriage. There were six Wigram children there. Seventeen servants including the visiting butler ran the household. The 1861 census has Peter, 76 years old and described as a cotton spinner, his wife Mary and unmarried daughter Fanny at Willersley Castle, with twelve servants. Only two of his brothers and sisters were still living: Joseph, a retired clergyman living at Mark Hall in Essex; and Frances who was residing at Oak Hill in Cromford. (Now Alison House, home to Toc H) Peter Arkwright died on 19 September 1866, aged 82. He had outlived all his brothers and sisters, his wife surviving him by almost six years. They are interred in the family vault in Cromford church. |

Left -

Left - |

|||

|

Frederic: 16 Aug 1806 - 6 Dec 1874. Frederic married Susan Sabrina, daughter of Venerable Archdeacon Burney on 4 Nov 1845. They had 3 children. Susan died in 1874. Mary Anne: 26 Sep 1807 - 1891. Mary married Robert Strange, a Scottish doctor. Edward: 15 Dec 1808 - 18 Dec 1850. Edward married Charlotte Sitwell on 24 April 1845. They had 3 daughters. Charlotte died in 1855. Francis: 17 Dec 1809 - 12 June 1812. Died in infancy. Henry: born 26 March 1811. Henry married 1) Henrietta Thorneycroft 2) Ellen Purves. He was the vicar of Bodenham in Herefordshire. Alfred: 19 June 1812 - 19 Jan 1887. Alfred married Elizabeth Critchley. He was a banker and lived at the Gate House, Wirksworth. By 1881 he had retired to Scarborough where he was a local magistrate. James Charles: 1st Oct 1813 - 16 May 1896. James married 1) Isabel Clowes 2) Mary Esther Broadhurst. In 1881 James and Mary were living in Westminster, London. Ferdinand William: 10 Dec 1814 - 14 Feb 1893 (?) Unmarried. Susan Maria: 11 Feb 1816 - 1864. Susan married Rev Joseph Wigram who became the Archdeacon of Winchester. Joseph's brother James married Anne; his sister Anne married Joseph, children of Arkwright Junior. Fanny Jane: 30 Aug 1817 - Nov 1894. Fanny married Darwin Galton of Claverdon, Warwicks in 1873. In 1881 they were living at Claverdon Leys, described as a mansion. Darwin Galton was a County Magistrate. Margaret Helen: 18 Dec 1818 - 1883. Margaret married her cousin James Wigram, (his mother was Anne, daughter of Arkwright Junior.) In 1881 they were living at Northlands, Wiltshire. James Wigram farmed 152 acres and was JP for the County of Wiltshire. Augustus Peter: 2 Mar 1821 - 6 Oct 1887. Augustus was a commander in the Royal Navy and MP for North Derbyshire from 1868 to 1880. He was unmarried. He is remembered on a brass plaque in Cromford Church. Octavius: 20 July 1822 - 9 April 1823. Died in infancy. John Thomas: born 2 Nov 1823. John married April 1856 Laura Willes. They lived at Hatton House, Warwickshire, where John was a Justice of the Peace and county Sheriff. Caroline Elizabeth: born 7 March 1825. Married J Clowes, the son of W L Clowes of Broughton Hall, Lancs. J Clowes was probably the brother of James Charles's first wife Isabel. Arthur: 2 Jan 1827 - 30 June 1827. Died in infancy. |

||||

|

16 Aug 1806 - 6 Dec 1874 Frederic Arkwright was the eldest of the sixteen children of Peter Arkwright and his wife Mary Anne. He was born on 16th August 1806 at Rock House in Cromford. Peter and Mary made considerable extensions to the house to accommodate their growing family. By the time they were able to move into Willersley Castle in 1843 following the death of Peter's father, Richard Arkwright Junior, the children had grown up, and most had left home. Frederic went away to boarding school at an early age, but being from a large extended family he had brothers and cousins at school with him, which must have made the break from home easier. In February 1816 he wrote to his parents from school in Seagrave in Leicestershire informing them that "George has left a box at Rock House with all his books in and I believe you will find it under the stairs". George was probably his cousin, son of Peter's brother Robert of Stoke Hall in Derbyshire. For a number of years he disappears from sight. He married Susan Sabrina, daughter of Charles Parr Burney, Venerable Archdeacon of St Albans, on November 4th, 1845. The census of 1851 records him living at Spondon, near Derby, with Susan and their three year old daughter Ellen Mary. They had two more children, Susan Alice, born in 1852, and Frederic Charles, born in 1853.

The family lived at Field House, which Frederic bought in 1850. |

||||

| Home || Community || Explore Cromford || News Archive || History || War Memorials || The Arkwrights || Poetry & Prose |

^Back to the top

Richard Arkwright was born in Preston, Lancashire, on 23 December 1732, the youngest of the seven surviving children of Thomas Arkwright, a taylor, and Ellen Hodgkinson. Richard received little education, and was apprenticed to a barber.

Richard Arkwright was born in Preston, Lancashire, on 23 December 1732, the youngest of the seven surviving children of Thomas Arkwright, a taylor, and Ellen Hodgkinson. Richard received little education, and was apprenticed to a barber. The first water-powered cotton spinning mill was speedily erected using stone from Steeple Hall near Wirksworth, and Arkwright's spinning machines soon came to be called Water Frames.

The first water-powered cotton spinning mill was speedily erected using stone from Steeple Hall near Wirksworth, and Arkwright's spinning machines soon came to be called Water Frames. Susanna was born at Bolton on 21st December, 1761.

Susanna was born at Bolton on 21st December, 1761.

Peter: 17 April 1784 - 19 Sept 1866. Peter married his cousin Mary Hurt in 1805. They had 16 children, 13 surviving. In 1806 Peter became a partner in his father's cotton business and lived at Rock House until inheriting Willersley Castle in Cromford.

Peter: 17 April 1784 - 19 Sept 1866. Peter married his cousin Mary Hurt in 1805. They had 16 children, 13 surviving. In 1806 Peter became a partner in his father's cotton business and lived at Rock House until inheriting Willersley Castle in Cromford.

Arkwright Junior kept an eye on the accounts until shortly before his death - and bringing up his large family at Rock House while his father occupied the grander Willersley Castle. He appears however, to have largely taken over the running of the Cromford mills, and to have carried out his duties as local squire and in the public arena conscientiously.

Arkwright Junior kept an eye on the accounts until shortly before his death - and bringing up his large family at Rock House while his father occupied the grander Willersley Castle. He appears however, to have largely taken over the running of the Cromford mills, and to have carried out his duties as local squire and in the public arena conscientiously. Up to the time of his father's death Peter and his wife Mary lived at Rock House in Mill Lane, opposite the Cromford mills. All their sixteen children were born there, and three had died there. Peter Arkwright extended their home considerably, adding a new 3-storey extension at the front. By the time he was able to move into Willersley Castle, the children had grown up, and most had left home.

Up to the time of his father's death Peter and his wife Mary lived at Rock House in Mill Lane, opposite the Cromford mills. All their sixteen children were born there, and three had died there. Peter Arkwright extended their home considerably, adding a new 3-storey extension at the front. By the time he was able to move into Willersley Castle, the children had grown up, and most had left home.